We Aren’t as Objective as We Like to Think

We love to think that our decisions are guided by logic, that we are rational data-driven neutral analysts, but that’s hardly the case.

Since the 1970s, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s work on cognitive biases shows that even the most rational among us rely on mental shortcuts when interpreting numbers, patterns, or trends. That means we see patterns where none exist, dismiss facts when they don’t align with our expected outcomes, and stick to conclusions long after evidence changes. The best part is that all of this happens… without us realizing.

To see this in action, try the short quiz below. It’s inspired by their research and designed to reveal which data bias might quietly shape the way you think! Try to answer with whatever comes to mind instinctively.

How Biased Is Your Brain?

Even our most “objective” decisions are filtered through subtle cognitive shortcuts. These aren’t necessarily bad, and I would go so far as to say that I sometimes rely on this intuitive, quick decision-making to guide me through uncertainty better than when I would overthink my way to an answer. The two psychologists I mentioned above, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, first mapped these mental shortcuts in a series of papers in the 1970s, eventually summarized in Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011). Their work asked a simple question: Why do smart people make systematically irrational judgments? The answer, in short: our brains run on two thinking systems.

System 1 — fast, automatic, intuitive.

System 2 — slow, deliberate, analytical.

System 1 is efficient but flawed, it relies on heuristics, mental rules‑of‑thumb that help us make quick decisions under uncertainty. While useful, these shortcuts often lead to predictable errors: cognitive biases. Many people think system 2 is superior. If you scroll to the end, you’ll find that I actually trust my System 1 more, but let’s go over that later.

Kahneman and Tversky identified three core heuristics that explain most everyday biases:

Representativeness: We assume one successful case or persona defines a whole pattern. We misinterpret the base rate, P(A | B) is NOT P(B | A).

Availability: We overreact to fresh, vivid metrics or viral moments. Classic recency bias, the easier something is to recall, the more significant it feels.

Anchoring and Adjustment: We let an initial number or baseline stick, which is okay, that’s why we have bayesian probability and a prior to start with. But this bias means we don’t properly or frequently update our prior, which then skews our liklihood estimation.

It’s very interesting the way these heuristics can manifest. With representativeness, we are overgeneralizing from a tiny sample. This is our love for clean categories which trick us into thinking “this one is typical” when statistically it probably isn’t. In data terms, our models fit past data but fall apart in new contexts. There is a really good example of this in How Not To Be Wrong (a book on math stats probability in real life).

Over time, behavioral economists expanded on their findings, adding more biases to the list:

Confirmation bias: our tendency to notice and trust information that supports our existing beliefs.

Sunk cost fallacy: continuing an endeavor simply because we’ve already invested time or money.

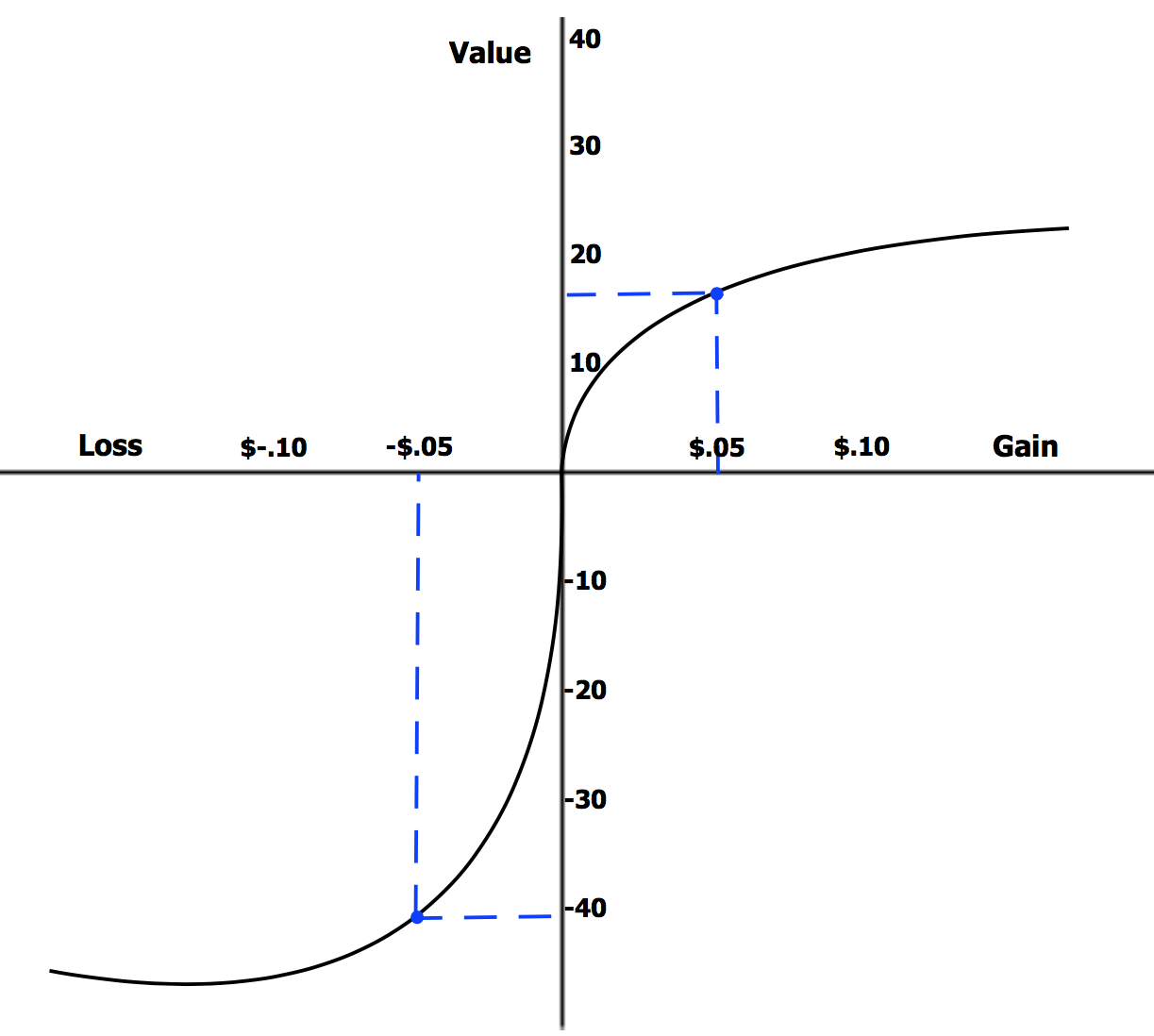

Loss aversion: valuing potential losses more than equal gains; introduced in Kahneman & Tversky’s 1979 paper on Prospect Theory. Very very interesting in my opinion.

One of my favorite topics is this loss aversion curve that reveals that we feel the pain of losing $100 about twice as strongly as we feel the pleasure of gaining $100. This creates a curve that’s steeper for losses than for gains. It crosses through the origin (the reference point) where outcomes flip from perceived gain to loss. Look below.

By Laurenrosenberger - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=67117183

Ah!!! The way this manifests in real life is also so very intriguing. Take for instance the dating life of a 20-something-year-old today. We all have heard the popular term “nonchalant”, what is it really? The person is being chill and not investing much because they’re minimizing potential loss at the expense of possible intimacy!!! That is loss aversion at its finest. It’s so cool, isn’t it?

And I think about that a lot in the context of data science (my day job) too, how much of our work is an attempt to hedge against loss. Every model is a way to shrink uncertainty into something we can explain. But reality never fits it perfectly. If somehow it does, sir… you know you are overfitting. You KNOW IT! There are always unobserved variables, context we don’t know, let alone measure, randomness we are unable to capture, people behaving in ways that defy every prior. Prediction, I think, by design, is an act of humility disguised as precision, at least for me. Someone with a keen interest in philosophy might retort and say that it’s our ego instead of humility, we aren’t saying there is stuff we don’t know, we’re saying we can model anything. True, that is ego. I concede.

So really, we only ever model a projection of the world, not the world itself. Life runs on too many dimensions la… feedback loops, emotions, coincidences, so much chaos. And ironically, the more we try to control for every factor, the more we discover how unstable the system really is. This makes me think that the future actually changes when we (try and) predict it, in fact it’s almost offensive to the world to try and boil it down to a formula. This discussion has long passed the discussion on biases, I know… but my blog my wish, haha.

So perhaps prediction science isn’t a way to master uncertainty but to be friends with it, you know? I am willing to admit that the signal will always remain beneath a layer of noise that I cannot trace. The most honest model is the one that prints, right next to its output: “This is our best guess, built by biased minds, trained on incomplete data, alive in an unpredictable world.” Obviously I won’t be doing this at work, that’s not what our clients retain us for, haha. To model is to admit that the universe runs deeper than our equations and still try to draw them anyway!!!

So to close, we’re led by decision heuristics all the time, no matter who we are and what we do. My personal take is to trust my System 1, somehow it just knows. With system 2, I’m stuck in a cycle of trying to account for EVERY SINGLE FACTOR out three, but this is impossible. System 2 believes, with all its might and heart, that it can create a logical, rational, wonderful model that predicts. I (humbly) scoff at that. It’s luck, it’s random, and on many days I find System 1 making better decisions for me than System 2… by the way, ironically I’m exhibiting a great example of confirmation bias. :)

Thank you for reading : )